David Ferrando Giraut

David Ferrando Giraut (Negreira, A Coruña, 1978) has a degree in Fine Arts from the Universidad Politécnica de Valencia and an MFA from Goldsmiths College, London. In 2010 he was one of the eight video artists selected for the LUX Associate Artists Programme in London. His work has been shown both in galleries and museums (The Green Parrot in Barcelona, Galería Bacelos in Madrid and Vigo, LABoral in Gijón, MARCO in Vigo, Tartu Kunstimuuseum in Estonia and the ICA in London, among others) and on film circuits (IndieLisboa, the Rotterdam Film Festival).

His work, centring mainly on video, sound and installation, stands at the intersection of various conceptual threads, such as the hybridization of natural elements, technology, and socio-political organization and its management throughout history; the tensions between representation and represented reality; the aesthetic experience as a cognitive tool; a questioning of the modern concept of temporality, and a search for continuity, employing notions such as transversality, Proustian reminiscence, ruin, and their parallels with audiovisual recording.

Images like ruins, inorganic images, immobile images, frozen images, perpetual, immutable images. Images that have been excised from the course of time, recorded by humankind for centuries using countless techniques; an exclusive and intrinsically human behaviour. But all incapable of capturing reality in all its complexity. Humans cling with absolute conviction to these images, giving them a central role in their lives and delegating to them a responsibility they can never fulfil. Because these images ultimately lack any kind of will or intention per se; only the human being who interprets them can instil a breath of life, if only for a fleeting moment.

How is our imaginary shaped? In what way is it like our existence? In what way is it different? Can we turn the assimilation of external references into a subversive act? David Ferrando Giraut proposes an exploration of these issues in works such as Cry Wolf (2007) or Night of the Living Dead (2006), videos that somehow emphasise the influence of cultural references mostly originating in the mass media. The question that arises as we become aware of this influence is how much of the responsibility lies with the image? And with the creator of that image? And with the spectator? And their mental images? Where do we put them? What place do they occupy in our lives? If, as Rancière says, “producing an image is always, at the same time, deciding about the capacity of those who will look at it”, the result becomes (for better or for worse) completely unpredictable.

These contradictions about the image and its inherent incapacity to represent faithfully a past that is gone are addressed by Loss (2011). The artist’s voice-over speaks of a past that he did not live and describes the objects that his parents brought with them from Venezuela in 1975 (before he was born): record player, records, home movies, a Super-8 projector. The narrative is suggestive of the story of Krapp, Samuel Beckett’s character who endlessly explores his past by playing a series of tapes on an old tape recorder. A past that seems alien to him, that he remembers little and poorly, and sometimes dislikes. Somewhere between weariness and melancholy. And so, very imperfectly, the images act as mediators between us and the reality that we slowly forget or have never known.

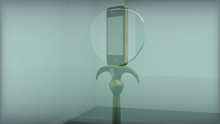

The work of David Ferrando Giraut uses allegory as a way of speculating on the relation between image and the reality it represents. In 2nd Nature (2014), images of a digitally generated ocean and vases from different epochs that are gradually integrated into that ocean manifest the contrast between nature and technology, reflecting on knowledge throughout history and the way we understand culture. Then, in another recent work, Catoptrophilia (2013), it is the minerals manipulated by humankind that serve to produce an image, a reflection, a mask. Polished obsidian, copper, bronze, silver, sheets of glass backed by aluminium or mercury. Elements capable of showing us an image that is ever more exact, but never perfect. The impulsive, persistent need to observe our face, turn ourselves into effigies, to exercise a stolen power, to colonize and therefore set ourselves at a distance. Attitudes that are maintained over the years, in spite of distances. How much coltan is needed to make all the mobile phones in the world? How many people have to die to achieve that?

Marla Jacarilla (visual artist and writer)